Basic: Alaska

Realities of Relocation

As temperatures across the Arctic rise at twice the global average, the impacts of climate change in Alaska are already being felt.1 Warming temperatures exacerbate problems of permafrost erosion, flooding, and

melting ice barriers, making an already unpredictable environment even more volatile. Alaska Natives are among the most impacted in this region, and, according to the Government Accountability Office, flooding

and erosion affects more than 200 Native Villages.2

As a consequence of the changing living conditions, Alaska Native communities are relocating their homes in what is the first wave of U.S. climate refugees. However, relocating is a culturally damaging, expensive,

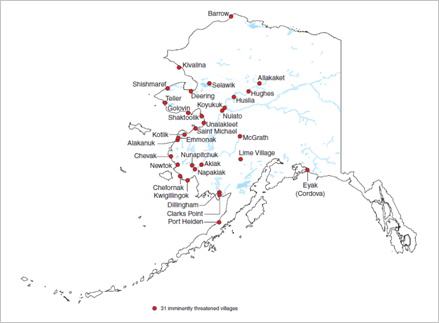

and politically complex process that few villages have begun. While a small number of Alaska Native communities are considering relocation, the situation continues to worsen: in a 2004 report, the GAO reported

that flooding and erosion imminently threatened four villages. By 2018, that number had risen to thirty-one villages.

Understanding Relocation

Extreme weather in Alaska is not a new phenomenon, and Alaska Natives are accustomed to adapting to its effects. Traditionally, many communities would adapt to the seasonal variability by migrating between hunting

grounds throughout the year. However, beginning around the turn of the 20th century, Alaska Natives were forced to settle in a single place by the U.S. government, creating a dependence on the immediate area and

subsequent vulnerability to events like erosion and flooding. This heavily influenced Native Alaskans’ subsistence harvests, as arbitrary borders were placed on their villages, serving as a restriction for

grounds on which harvests are gathered. Climate change creates more extreme seasonal events, increasing the risk associated with living in one place, including erosion of permafrost foundations on which many

communities are built.3

Alaska Native communities are at varying stages in considering relocation, and have very different perspectives of what relocation will mean. While some individuals may look forward to improved living

conditions, others are reluctant to abandon the lands their ancestors lived on for thousands of years.4 The primary efforts of Alaska Natives, however, are often focused on securing food and shelter for their

families, making planning for long-term changes more challenging.

Communities that have decided to relocate are at varying stages in the process, and slowed down by a number of challenges, including choosing a relocation site, paying for the process, and partnering with government

organizations to develop plans for their relocation. Additionally, uprooting and moving to a new land represents breaking from uniquely adapted traditions that took thousands of years to develop.

The situation is further complicated by finding a site that is both culturally acceptable and structurally sound. Alaska Native communities are located in some of the most remote places in the world and are

often only accessible by airplane. As a result, the cost of relocating several hundred people climbs into the hundreds of millions of dollars. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) estimated the cost of

relocating the Village of Kivalina at $95-125 million, Shishmaref at $100-200 million, and Newtok at $80-130 million. These costs are well beyond what is realistic for subsistence communities, so most turn

to government agencies for funding support. Unfortunately, there are a myriad of political, cultural and economic factors that complicate obtaining government funding for relocation. For example, the USACE

has to justify its projects by performing a cost evaluation that shows that expected benefits outweigh the cost. However, estimating the cost of preserving some of the oldest cultures in the world and

their ties to the land are complex.

Another complication arises from Alaska’s political jurisdictions:

"Because of Alaska’s unique structure of organized boroughs and an unorganized borough, unincorporated Native villages in the unorganized borough do not qualify for federal housing funds from HUD’s (U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development) Community Development Block Grant program. The disqualification of the villages in this borough is not because they lack the need for these funds, but because

there is no local government that is a political subdivision of the state to receive the funds." Even funding specifically aimed to address these types of situations is sometimes unavailable to communities:

"The Federal Emergency Management Agency has several disaster preparedness and recovery programs, but villages often fail to qualify for them, generally because they may lack approved disaster mitigation

plans or have not been declared federal disaster area." Native Villages undergoing relocation, managed retreat, or protect-in-place efforts struggle to receive necessary funding and resources. These

challenges can often be attributed to the tediousness of bureaucracy when navigating the different federal and state departments awarding funding.

Agency Support

Owing to the economic and technical dynamics of relocation, communities are reaching out to government organizations for assistance. The State of Alaska is addressing the need for such assistance and in

2007 created the Climate Change Sub-Cabinet, which has participated in the preparation and implementation of a climate change strategy for Alaska.5 Information made available on the State of Alaska climate change website

(https://www.commerce.alaska.gov/web/dcra/climatechange.aspx) addresses adaptation, mitigation, immediate actions and

research needs. At the Federal level, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been working closely with communities to help develop strategies and provide technical support for relocation. However, the lack of a lead

federal entity to coordinate and help prioritize assistance to relocating villages creates many problems with miscommunication and undirected efforts.

Alaska Native Villages Engaged in Relocation Efforts

A 2018 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) identified 31 Alaska Native Villages as imminently threatened by coastal erosion, flooding, and rising temperatures.

Source: 2018 GAO report, pg. 4

Source: 2018 GAO report, pg. 4